‘This Parliament of Monsters’: London’s spectacular fairs

This is the text of a talk I gave on 7 September at ‘Reclaiming Spectacle’ – the two-day finale of the 2013 Congress for Curious People. There’s a short bibliography of sources at the end, and I’m quite happy to provide detailed references on request.

‘Fairs are unnecessary, are the cause of grievous immorality, and are very injurious to the inhabitants of the towns where they are held.’ These stern, high-collared words from the Metropolitan Fairs Act 1871, which within a year had closed down London’s few remaining medieval fairs, seem to capture the very essence of humourless Victorian rectitude, the desire to clamp down on the pleasures of the multitude. For a generation of left-leaning social and cultural historians (and is there any other kind?) the decline of the fairs marked a great shift in British society, as it came decisively under the influence of industrial capitalism, the modern state, and the embourgeoisement of the working classes.

As a left-leaning cultural historian myself this is a view with which I’m very familiar. But in keeping with the spirit of this conference I want to put it aside and tell a different kind of story, one that is more attentive to these elusive and multitudinous pleasures. This story begins with another exponent of solemn Victorian grandiloquence: William Wordsworth. In the 1805 version of ‘The Prelude’ Wordsworth recounted a visit to:

… the Fair

Holden where Martyrs suffered in past time,

And named of Saint Bartholomew; there, see

A work that’s finished to our hands, that lays,

If any spectacle on earth can do,

The whole creative powers of man asleep! …

…What a hell

For eyes and ears! what anarchy and din

Barbarian and infernal, – ’tis a dream,

Monstrous in colour, motion, shape, sight, sound!

Colour, motion, shape, sight, sound – the grain of speech and action, sweat and spit, glitter and bruises, cursing and hooting: these are the lineaments of a sensual history of London’s fairs. More than any other kind of history, this calls upon our powers of imagination and sympathy. Following Richard Holmes in his influential (but to my mind extensively over-praised) Footsteps: Adventures of a Romantic Biographer, the very most we can hope is to hear the echoing laughter of our subjects as they recede into the gloom of history’s corridors.

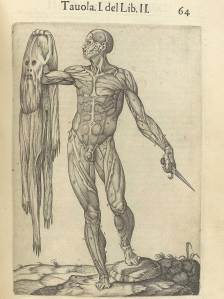

The closest I’ve come in finding a symbol for this endeavour is Hogarth’s ‘The Laughing Audience’. As these Hanoverian pleasure-seekers would have known in their bones, the fair was a place of fleeting encounters, vivid pleasures, and the (temporary) dissolution of the bonds of mundane life. So as I try to look through the eyes of these people I’m going to be deliberately untheoretical, deliberately shallow, deliberately distracted by the loud, the cheap, the garish, and the vulgar. For reasons I’m quite sure you will understand, I’m taking Hogarth – born and raised a stone’s throw from the heart of Bartholomew Fair – as the patron saint of this story. Though St Bartholomew himself would be equally apt. One hagiography has him martyred by being skinned alive, and his flayed skin has become his major iconographical attribute – Bartholomew as écorché wearing his skin as a kind of Herculean cloak.

(As many of you will know, this is a trope repeated in the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel and in Renaissance anatomical treatises like Juan Valverde de Amusco’s Historia de la Composicion del Cuerpo Humano – but that is a story Joanna Ebenstein can tell far better than I.) Theologians read this as a symbol of penitent suffering through exquisite pain, but for our purposes Bartholomew embodies the double face of spectacle: the concealing skin of propriety removed to reveal the raw surfaces of human life – all the fun of the fair.

First – because the social historian in me insists on having his say – a few words of context. The earliest fairs were quite literally gaudy and tawdry affairs. Fair derives from the Latin word feria – a holiday. Gaudy from gaudium – joy, the joy attendant upon celebrating a saint’s day. And tawdry from St Audrey – an East Anglian saint who gave her name to cheap and gaudy lace collars sold at fairs. As Ronald Hutton has pointed out, the notion that fairs represent a substantial survival of pre-Christian practices tells us much more about the preoccupations of late Victorian anthropologists than it does about the historical record. Most began as gatherings of pilgrims on saints’ days, attended by tented communities of traders and showmen. Some are known to date from Anglo-Saxon times, but after the Norman Conquest these regular gatherings acquired new importance in the selling of goods and the hiring of servants and labourers. Stourbridge Fair, for example, established in 1199 with a charter from King John, quickly became the largest trading fair in Europe.

Held over three days around the Feast of the Holy Cross on 14 September, Stourbridge raised funds for a colony of lepers outside Cambridge, and provided the inspiration for ‘Vanity-Fair’ in John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress. London’s three great fairs – Bartholomew Fair, Southwark Fair, and St James’ Fair (later the May Fair) – all emerged from this union of commerce and Christianity. A charter from Henry I in 1133 gave the Priory Hospital of St Bartholomew the right to hold a three-day cloth fair around St Bartholomew’s Day on 24 August, alongside the Corporation of London’s cattle fair at Smithfield. Lacking the great open space of Smithfield, Southwark Fair, chartered by Edward IV in 1462 and originally called ‘Our Lady Fair’, took place in the courts and inns off Borough High Street around 7 September. And from 1290 the maiden lepers of St James the Less held a fair on the eve of St James’ Day, 25 July, in the marshy ground beside their hospital – now St James’ Park.

These three great fairs were accompanied by dozens of smaller gatherings, in Westminster, Hampstead, Croydon, Edmonton, Stepney, Mitcham, Bow, Deptford, Greenwich, Barnet, Blackheath, Peckham, and many others. But by the seventeenth century the same forces of mercantile capitalism that had called the fairs into existence were driving them away from business and towards pleasure. The Dissolution of the Monasteries in the 1530s destroyed the hospitals and religious houses they had been created to support, and the old, annual trading fairs were simply irrelevant in a world dominated by international trading partnerships like the Hanseatic League and the Dutch and English East India Companies. The ‘Bartholomew Fayre’ taken by Ben Jonson as a setting for his 1614 comedy was no three-day cloth fair but a two-week festival of entertainment and loose living. Patches of open ground like Smithfield and Charterhouse had often served a darker purpose as scaffolds or plague-pits; as was so often the case, Londoners mounted their revels over the bones of the dead.

If we want a symbol for this transformation, we need look no further than the River Thames. Slowed by the arches and waterwheels of Old London Bridge, and chilled by the fierce winters of the Little Ice Age, the Thames froze repeatedly between the late sixteenth century and the early nineteenth century. Londoners were not slow to capitalise on the traditional freedoms of life on the river. Elizabeth I watched displays of archery and dancing on the ice in 1564 (a scene imagined by Virginia Woolf in the early chapters of Orlando). In early December 1683 the river froze to a depth of eleven feet, but within days the ice held an entire street of taverns and stalls, with sledging, skating, bear-baiting, ninepins, a printing press, a whole ox roasted, a printing-press, and (according to one observer) ‘all manner of debauchery’. These frost fairs continued through the eighteenth century – in 1788 the entertainments were said to have run continuously from Putney Bridge to Rotherhithe – and came to an end only with the demolition of Old London Bridge in 1831.

The frost fairs embodied the new face of London’s fairs. Not arenas for commerce or trade, but the pursuit of pleasure and spectacle in a space that came and went: London at play. With this new emphasis on pleasure and spectacle came a new moral ambivalence. Though it survived the Puritan Commonwealth, St James’ Fair was suppressed in 1664 ‘as tending rather to the advantage of looseness and irregularity rather than to the substantial promotion of any good, common and beneficial to the people’. Granted a new licence by James I in 1689, and moved to May Day, it now revolved around duck-hunting on the lake in St James’ Park, and was suppressed again by the Grand Jury of Middlesex in 1708.

Here we can see, amongst other things, the influence of the Society for the Reformation of Manners – the shock troops of the respectable ‘middling sort’ at the beginning of the Enlightenment, aiming to sweep away the hedonistic liberality of Restoration England and replace it with a plainer, narrower, more pious vision of public morality. Dominated by clergymen, magistrates and MPs, the Society paid a network of constables and informers to collect evidence against drunkards, pimps, prostitutes, sodomites, gamblers, trouble-makers and Sabbath–breakers. Despite this – perhaps because of it – the first half of the eighteenth century is acknowledged to be the zenith of London’s spectacular fairs. The fair season began on May Day with the May Fair, revived in 1738 by one Mr Shepherd on the site of his cattle market off Park Lane (hence the modern Shepherd Market) and continued through the heat and dust of the summer to Southwark Fair in late September. As the wealthy withdrew to Richmond or Twickenham, the poor had more of the City to themselves.

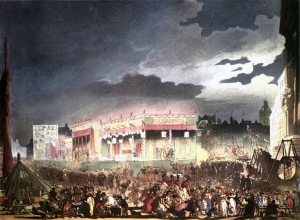

So if we could step into Hogarth’s ‘Southwark Fair’ (1734) – an allegory in which, as Jenny Uglow has noted, everyone and everything is falling, pleasurably – what would we see, what would we hear, what would we taste and smell?

Two clichés are useful here. Quite apart from the fairs, Enlightenment London was – as Richard Altick showed a generation ago – a city of spectacle, in theatres and pleasure-gardens, coffee-houses and operas, cricket-matches and brothels. As the British began their global adventure of commerce and conquest, groups of Iroqois, Cherokee and Eskimos were put on display in the imperial capital. And the governors of Bedlam made up to £400 per year from those who paid to see the inmates. London was also a city of great violence, a place in which the public destruction of human and animal life was entirely commonplace. As in the figure of St Bartholomew, spectacle and violence were always imbricated; show-booths and stages were paralleled by scaffolds and gallows, stocks and cages, bear-baiting in Bankside, cock-fighting in Westminster. So far from being unparalleled eruptions of brutality and chaos, the fairs held – in Hamlet’s words – the mirror up to nature, offering a more-or-less faithful reflection of daily life in London.

Fairs were a grand spectacle filled with smaller spectacles, and in the eighteenth century the most popular of these were plays. Many had something in common with the medieval tradition of mystery plays: a 1702 production of The Creation of the World at Bartholomew Fair showed all of human history from Adam and Eve via Imperial Rome to Marlborough’s victories in the War of the Spanish Succession. According to the playbill:

A multitude of angels will be seen in double rank, which presents a double prospect, one for the scene, the other for the palace, where will be seen six angels ringing of bells. Likewise machines descending from above, with Dives rising out of Hell and Lazarus seen in Abraham’s bosom, besides several figures dancing Jiggs, Sarabands, and Country Dances to the admiration of the spectators, with the merry conceits of Squire Punch and Sir John Spendall, completed by an entertainment of singing and dancing with several naked swords by a child eight years of age.

Other plays at Bartholomew Fair included ‘The Loves of the Heathen Gods’, ‘The Siege of Troy’, ‘The Rash Vow’, ‘Tamerlane the Great’, and ‘The Cruelty of Atreus’. Again from the playbill:

… the scene wherein Thyestes eats his own children is to be performed by the famous Mr Psalmanazar, lately arrived from Formosa, the whole supper being set to kettle-drums.

Some of the larger West End theatres closed during the summer and took their productions to this large and restless audience. Reciprocally, the fairs had their own influence on the London stage. Mr Walker, the original Macheath in John Gay’s Beggar’s Opera, was discovered playing a part in ‘The Siege of Rhodes’ at Bartholomew Fair, and Henry Fielding cut his theatrical teeth running a fair show-booth in the 1720s. At the end of the century the actor and impresario John Richardson performed at the London fairs with costumes and scenery taken from Drury Lane, and Richardson’s Theatre continued to tour until 1853. But the supremacy of the theatrical booth at Bartholomew Fair had come in the 1750s, with the shortening of the fair from two weeks to three days. It was hardly worth assembling a troupe and rehearsing a play for such a short run, and by the late eighteenth century other kinds of spectacle had come to the fore. Again, Wordsworth gives us a sense of what we might have seen:

… Albinos, painted Indians, Dwarfs,

The Horse of knowledge, and the learned Pig,

The Stone-eater, the Man that swallows fire,

Giants, Ventriloquists, the Invisible Girl,

The Bust that speaks, and moves its goggling eyes,

The Wax-work, Clock-work, all the marvellous craft

Of modern Merlins, Wild Beasts, Puppet-shows,

All out-o’-the-way, far-fetched, perverted things,

All freaks of nature, all Promethean thoughts

Of man …

Puppet-shows could be comparatively highbrow affairs – ‘Phaeton’s Fall’, ‘The Story of the Chaste Susannah’, ‘The History of Solomon and the Queen of Sheba’ – but the staple was of course Punch, described by Blanchard Jerrold as ‘the oftenest performed serio-comic drama in the world … an unbroken round of facetious brutalities’. As any child traumatised by a Punch and Judy show will tell you, puppet-shows could also be unsettlingly macabre affairs. In The Amusements of Old London William Biggs Bolton described one eighteenth-century show at the May Fair:

… a shutter was fixed horizontally, upon which a puppet laid his head. After much formality, it was decapitated by another puppet, armed with a portentous axe. Sidney, Raleigh, Charles I, Russell, and other martyrs of history, bled thus again in effigy through many years.

Waxworks provided an equally gruesome spectacle. Through the early eighteenth century Mrs Salmon’s waxwork booth at Bartholomew Fair featured the usual selection of anatomical and pathological specimens, portrait busts, and clockwork tableaux, the most popular of which was the execution of Charles I. Side-shows featuring live performers could be no less curious. One performer at Southwark Fair undertook ‘to drive about forty twelve-penny nails into any gentleman’s breech, place him in a lodestone chair, and withdraw them without the least pain’. At the May Fair a Frenchman exhibited his wife:

… a thin woman of much beauty, raising an anvil with her hair, and supporting the same implement on her breast, while a company of three blacksmiths forged a horse-shoe upon it with the usual heavy hammers.

The skies, too, were filled with spectacle. Southwark Fair specialised in acrobats and daredevils: Mr Cadman, who walked on a tightrope from the tower of St George’s Church to the Mint, and the Violantes, who made a speciality of sliding down slack ropes from church towers and steeples (both of whom appear in Hogarth’s ‘Southwark Fair’. Just as important as these death-defying performances were the stories told about the performers. One ‘Lady Mary’, a tightrope-walker at Southwark Fair ‘whose beauty attracted and whose modesty resisted the gilded youth of a generation’, was said to be:

… the daughter of a Florentine noble, who eloped with an English acrobat named Finley and married him, learned his trade, and helped to support him until her career was ended in tragedy, when she fell in 1703 and died a day or two later.

Lady Mary’s demise was, sadly, far from rare. Two years before Hogarth made his print a ‘flying man’ died in a fall from the tower of St Alphege in Greenwich, and many others met their ends when ropes frayed or knots came loose.

By the early nineteenth century beasts were supplanting puppets and flying-men as the most lucrative attraction at London’s fairs. In 1827 Wombwell’s Menagerie was the highest earner at Bartholomew Fair, making £1700 compared with £1200 for Richardson’s Theatre. Menageries had been a popular attraction since medieval times; Ben Jonson in Bartholomew Fair mentions ‘the blacke Wolfe, and the Bull with the five legges, and two pizzles; … And the dogges that daunce the Morrice, and the Hare of the Tabor …’, and in 1660 the diarist John Evelyn recalled dancing monkeys at Southwark Fair:

They saluted one another with as good grace as if instructed by a dancing-master; they turned heels over head with a basket having eggs in it without breaking any; also with lighted candles in their hands and on their heads without extinguishing them and with vessels of water without spilling a drop.

By the early eighteenth century more exotic creatures were making their debuts. From just one advertisement for a menagerie at Bartholomew Fair we hear of:

The Noble Cassowary brought from the Island of Java in the East Indies … He eats iron, steel and stones, and he hath two spears grown by his sides … a leopard from Lebanon … a possum from Hispaniola … an eagle from Russia … a rattlesnake of a very large size, and rattles that you may hear him a quarter of a mile almost … a surprising young mermaid, taken on the shores of Acapulco, that the generality of mankind believe there is no such thing … [and] a little black hairy monster, bred in the deserts of Arabia – a natural ruff of hair about his face, walks upright, takes a glass of ale in his hand, and does several other things to admiration.

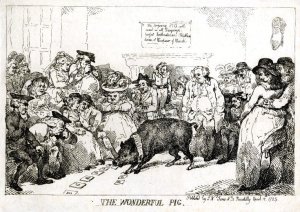

‘Noble Cassowaries’ and ‘little black hairy monsters’ never lost their appeal, but by the end of the century fair-goers were thrilling to displays of bestial rationality. The ‘Learned Pig’ made his London debut in the spring of 1785, after touring genteel resorts in the north the previous summer. Described as ‘Well-versed in all Languages, a perfect Arithmetician & Composer of Musick’, this porcine marvel caught the attention of Samuel Johnson through a conversation with Anna Seward, the ‘Swan of Lichfield’. According to Boswell, Johnson mused that:

… the pigs are a race unjustly calumniated. Pig has, it seems, not been wanting to man, but man to pig. We do not allow time for his education, we kill him at a year old.

The Learned Pig seems to have sparked a small craze for educated animals: Toby the Sapient Pig appeared at the London fairs between 1818 and 1823, along with Pinkey, ‘a learned and scientific goose’. And at Bartholomew Fair in 1829 Signor Capelli trumpeted the virtues of his ‘Learned Cats’:

The Cats will … beat a drum, turn a spit, grind knives, play music, strike upon an anvil, roast coffee, ring bells, set a piece of machinery in motion to grind rice in the Italian manner … [also] The Wonderful Dog will play any gentleman at dominoes that will play with him.

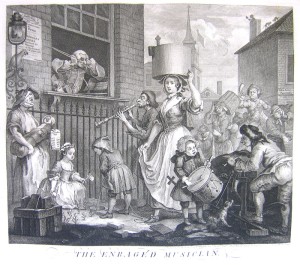

In the presence of so many specimens of brute nature – human and animal – it is hardly surprising that Wordsworth complained of:

… buffoons against buffoons

Grimacing, writhing, screaming, – him who grinds

The hurdy-gurdy, at the fiddle weaves,

Rattles the salt-box, thumps the kettle-drum,

And him who at the trumpet puffs his cheeks …

A century earlier Ned Ward, in his London Spy, had characterised the sound of Bartholomew Fair as:

… the rumbling of Drums, mix’d with the Intolerable Squeakings of Cat-calls, and Penny Trumpets, made still more terrible with the shrill belches of Lottery-pick-pockets, thro’ Instruments of the same Metal with their Faces …

Ward also gave a striking and rare description of the fair-going crowd itself:

Some companies were so very oddly mix’d, that there was no manner of coherence between the Figure of any One Person and another: One perhaps should appear in a Lac’d-Hat, Red-Stockings, Puff-Wig, and the like, as Prim as if going to the Dancing-School. The next a Butcher, with his Blue-Sleeves and Woollen Apron, as if just come from the Slaughter-House. A Third, a Fellow in his Yorkshire Cloth-Coat, with a Leg laid over his Oaken Cudgel, the Head of which being a Knot of the same Stuff, as Serviceable as a Protestant Flail, and as big as a Hackney Turnip.

Ballad-sellers had always been a staple of London’s fairs, and Ben Jonson gave a flavour of their offerings in Bartholomew Fair:

A delicate ballad of the Ferret and the Coney.

A preservative against the Punques evill.

Goose-greene-starch, and the Godly garters.

The Wind-mill blowne downe by the witches fart!

Ballad-sellers mingled with the criers of plays and side-shows, as in this extract from an account of Bartholomew Fair in 1698, attributed to one ‘Monsieur Sorbière’ but in fact a satire on British mores by the English hack William King:

I met a man that would have took off my Hat, but I secur’d it and was going to draw my Sword, crying out ‘Begar! Damn’d Rogue! Morbleu!’ &c., When on a sudden I had a hundred people around me, crying ‘Here, Monsieur, see Jeptha’s Rash Vow’; ‘Here, Monsieur, see The Tall Dutchwoman’, ‘See The Tiger’, says another; ‘See The Horse and No Horse whose Tail stands where his head should do’; ‘See The German Artist, monsieur’; ‘See The Siege of Namur, Monsieur’: so that betwixt Rudeness and Civility, I was forc’d to get into a Fiacre, and with an air of haste and a full trot, got home to my lodgings.

While a cacophony of trumpets, dogs and aggrieved Frenchmen assaulted the ears, the aroma of roast pork and fresh gingerbread beguiled the nostrils. Many sources agree that gin, gingerbread and roast pork were the staples of fair-goers – though in Jonson’s Bartholomew Fair one character shouts at another ‘You stinke of leeks, Metheglyn, and cheese, you Rogue’. Pork also served as a metaphor for the grosser human appetites expressed at the fair. The villain of Jonson’s play – Zeal-of-the-land Busy, a canting, hypocritical Puritan – takes a mouthful of pork to prove that he is not a concealed Jew, only to be discovered in a later scene having devoured two whole pigs. This democracy of pleasure reveals the glutton and the sensualist in even the hottest Puritan.

If my inner social historian were to take up the story again at this point, it would be to sketch a long, slow decline from this peak of pleasurable spectacle. Through the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries new kinds of genteel rational recreation – the Holophusikon, the Cosmorama, the Cyclorama, dioramas, the Egyptian Hall on Piccadilly, the Great Exhibition – took the place of the fairs in London’s calendar of spectacle. For Wordsworth, at least, this went hand in hand with the falling-away of his youthful revolutionary passion. Compare the outraged fascination of his lines on Bartholomew Fair with the dry, didactic, improving tone of his description of a visit to ‘a cabinet or wide museum’ during his time at Cambridge:

And though an aching and a barren sense

Of gay confusion still be uppermost,

With few wise longings and but little love,

Yet something to the memory sticks at last,

Whence profit may be drawn in times to come.

But I would rather end by trying to imagine what we would be thinking as we stepped out of Hogarth’s ‘Southwark Fair’. We would be footsore, deafened, stuffed with roast pork, gin and gingerbread, quite possibly pickpocketed. We might have seen a pig do sums, a man have nails pulled from his bottom with a magnet, a woman fall to her death from a tightrope, the execution of a puppet, the mocking of a fop, and the entire history of the world declaimed in rhyming couplets. We would have walked the fine line between a crowd and a mob, between a galvanising performance and an incitement to riot. Put abstractly, we would have taken part in London’s long argument over the question of how to be civilised, of what should be permitted and what excluded from the crowded communal life of a city. We might wish to challenge Matthew Arnold’s High Victorian opposition between culture and anarchy, and think instead about anarchy as culture. Put more simply, we would have been entertained, quite spectacularly.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Richard D. Altick, The Shows of London, Belknap Press, 1978

William Biggs Bolton, The Amusements of Old London [1901], 2 vols, Cambridge University Press, 2011

Gustave Doré and Blanchard Jerrold, London: A Pilgrimage [1872], Anthem Travel Classics, 2005

Richard Holmes, Footsteps: Adventures of a Romantic Biographer, new ed, HarperPress, 2012

Ronald Hutton, The Stations of the Sun: A History of the Ritual Year in Britain, Oxford University Press, 1996

Ben Jonson, Bartholomew Fair: a Comedy [1614], in The Alchemist and Other Plays (ed. Gordon Campbell), Oxford World’s Classics, 2008

Jenny Uglow, Hogarth: A Life and a World, new ed, Faber & Faber, 2002

Ned Ward, The London Spy [1709 ed.] (ed. Paul Hyland), Michigan State University, 1993

Ben Weinreb et al, The London Encyclopaedia, third ed, Macmillan Reference, 2010

William Wordsworth, ‘The Prelude’ [1805 ed.], in The Prelude: The Four Texts, Penguin Classics, 1995

Excellent, quite well-researched and lively! The Learned Pig and his heirs and successors carried on quite a while — in the UK the act seems to have faded in the 1830’s, but in the US is persisted even into the 20th century … it was Altick (and Ricky Jay) who first brought Toby to my attention, and were the germs of the story as told by Toby himself in my 2011 novel.

Pingback: Death, madness and amorphous blobs at the Congress for Curious People | Rich Pickings

This was a brilliant talk, thank you. Included in an event write up here http://pickingrich.wordpress.com/2013/09/27/death-madness-and-amorphous-blobs-at-the-congress-for-curious-people/

Thank you! Glad you enjoyed it.